My Hawaiian Language Journey: Learning Olelo Hawaii

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning I receive commissions for purchases made through those links at no cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

Table of Contents

Despite being born and raised on Maui, I never learned the Hawaiian Language, ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i.

Back in the 80s, we had a kupuna who visited our school once a week to teach us things like the words for colors or simple chants, maybe. It was all around us of course, in music and something you’d see on all the street signs or place names, but not something I’d hear often in everyday conversations.

What I didn’t fully grasp as a kid was that this wasn’t entirely by accident. In fact, Hawaiian was once banned in schools. A few years after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, English took over as the language of business, government, and education, and kids who spoke Hawaiian in school were even punished for it.

There was a Hawaiian language renaissance in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until 1987 that the ban was finally lifted officially, and efforts to bring the language back began. (Which is maybe how we ended up with our limited once-a-week study in my elementary school!) In 2022, the State of Hawaii formally apologized for the 1896 ban.

Fast forward to today, I’m learning Olelo Hawaii as an adult. As an online ESL teacher, I spend my days helping students gain confidence in English—but as a language lover myself, I’m on the other side, starting from scratch with ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i.

In this post, I’ll share:

- A brief history of ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i and why it nearly disappeared

- My own journey learning Hawaiian for the first time

- Why keeping languages alive is so important

- Some of my favorite resources for learning Hawaiian

If you’ve ever wanted to learn Hawaiian—or maybe if, like me, you grew up in Hawai‘i but never really learned it—I hope this gives you a place to start.

1. A Brief History of ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i

Hawaiian was once the dominant language of the islands—spoken at home, in schools, in government, and in everyday life. There were Hawaiian-language newspapers establisted in the 1830s and a high degree of literacy in the population. But after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, that changed quickly.

By 1896, a law was passed banning Hawaiian from being taught in schools. English became the language of instruction, and over time, speaking Hawaiian became seen as something outdated, even shameful. Many elders today still share stories of being punished for speaking their native language in class.

Even before this law, the rise of sugar plantations had already been pushing English to the forefront. My great-grandparents lived in the sugar camps of Pu‘unēnē and Pā‘ia, where workers from Japan, China, the Philippines, and Portugal all had to communicate with each other—and with their plantation bosses, who spoke English.

Even the first languages of the plantation workers blended into a Hawaiian Creole we call Pidgin out of a necessity to find a common language. My grandmother went by Charlotte, rather than her Japanese name, Nobuko and my grandfather was known as Clarence, rather than Hideo. My father never learned any Japanese from my grandparents.

For nearly a century, English ruled and Hawaiian fluency declined. But in 1987, the ban was finally lifted, and in the years since, Hawaiian immersion schools, university programs, and community efforts have worked to revitalize the language. Today, Hawaiian is still considered endangered, but its presence is growing!

In 2024, a woman made an ignorant and dismissive comment that Hawaiian is a “dead language” after another testified in Olelo Hawaii (then translated to English) at a Honolulu City Council hearing and it caused quite the backlash! In fact, Hawaiian and English are both recognized as official state languages and Hawaiian is very much alive!

2. My own journey with learning ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i

Despite growing up in Hawaii, my experience with Hawaiian was mostly limited to words, not conversations. In elementary school, we learned basic Hawaiian vocabulary—colors, numbers, maybe a few simple chants. But it was never something we were encouraged to speak fluently.

When I got to high school, I had the option to take Hawaiian as a foreign language (ironic, right?) But sadly, I never really considered it. I was encouraged to take Japanese instead and that made sense, given my family background. Plus, at the time it was practical for work in tourism and one of my after school jobs was as a “bilingual greeter” for Japanese visitors to Maui Coffee & Candy Factory.

Maybe because I’ve always been drawn to impractical and far-away daydreams, I also chose to study French. (For one year, I even had Japanese and French classes back-to-back, which really felt like a mental workout!)

But Hawaiian? I’m embarrassed to admit I never learned more than the basics.

Now, as an adult, I’m learning for the first time. Maybe it’s because I’ve spent the past few years teaching English as a second language, and studying other languages during my travels. Learning the native language of a place really opens up new layers of understanding and it’s been interesting to look back at my home through this new lens.

One of my favorite discoveries so far? Day to day life from “talk story” recordings and things like Hawaiian food vocabulary. I love coming across words for ingredients and cooking methods. There’s something about listening to the basic steps of a recipe (in any language) that help with the repetition and vocabulary.

3. Keeping Languages Alive

Did you know that of the 7,000+ languages spoken in the world today, nearly 40% are considered endangered? Some are already disappearing at an alarming rate—often because of colonization, globalization, or policies (like the one in Hawaii) that force a dominant language on people.

Keeping a language alive isn’t just about words and grammar—it’s about culture, identity, and history. So for me, learning ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i isn’t only about personal curiosity. It’s about honoring the people who fought to keep their language alive and doing my part (however small) to continue their effort.

One person I have enjoyed following is Sophia Smith Galer, a journalist who covers language extinction and linguicide. She’s currently writing a book called How to Kill a Language, and she frequently reports on linguicide for the BBC and on social media.

4. ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i Resources

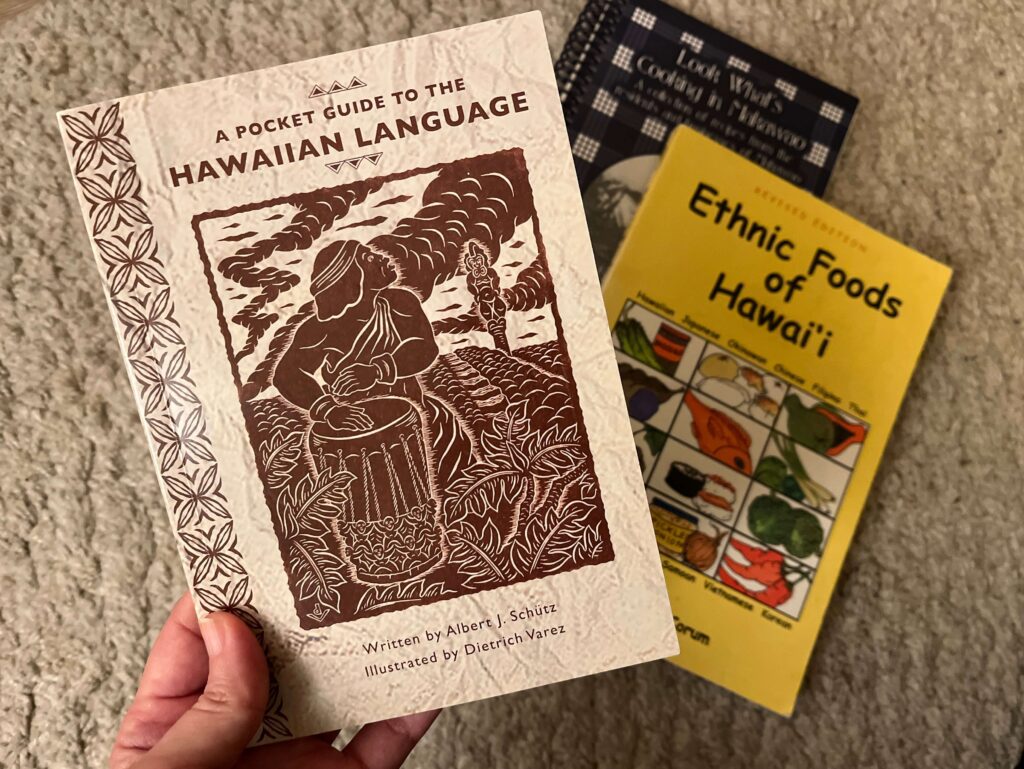

If you’re interested in learning Hawaiian or about the history of Hawaii, here are a few places to start:

- Duolingo – this popular language learning app offers many endangered languages, including Olelo Hawaii. While the course is not the most robust, I did learn sentence structure and quite a bit of vocabulary in going through it’s levels. The gamification aspect helps to remind me to study for at least a few minutes once a day.

- Manaleo Archives – recorded clips of kupuna discussing memories and talking about daily life and traditional Hawaiian knowledge on a variety of topics, even things like crab fishing!

- Ulukau.org – Hawaiian Language Dictionaries and archives of newspapers and other resources in Olelo Hawaii.

- Ka Alala YouTube Channel – I appreciate the emphasis on education and on spoken Hawaiian language. He also shares interviews with native speakers on topics that are quite interesting, for example for me with cooking vocabulary I enjoyed hearing him narrate “How to fry an egg” in Olelo Hawaii. He has a full resource page as well.

- Kaulumaika – A wonderful resource page for those who want to deepen their learning through the intersection of art, crafts like drawing or sewing, and resources about native plants. Emily & her husband Maluhia (who runs Ka Alala, above) also have a podcast, Hawaiian at Home, following their Hawaiian language journey as a family.

- Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen (Queen Lili‘uokalani’s Biography) – Queen Liliuokalani was the last reigning queen of the Hawaiian Kingdom. She purposely chose imprisonment in her own palace rather than risking bloodshed of her people against the businessmen who had overthrown her government. She appealed to the American government and wrote her own autobiography to tell her story in her own words. For me, whenever I pass I’olani Palace, I’m still saddened seeing the window shade drawn in the room where she was held. It is powerful to read her autobiography to hear her story in her own words.

- Finding Meaning: Kaona and Contemporary Hawaiian Literature by Brandy Nālani McDougall – Kaona is the hidden meanings that are often poetic and multi-layered in olelo no’eau (proverbs), mo‘olelo (literature and histories), and mooku’auhau (genealogies). This book traces references in contemporary literature and references to traditional Hawaiian literature and stories like the Kumulipo. Highly recommended!

- ‘Ōlelo No‘eau: Hawaiian Proverbs and Poetical Sayings by Mary Kawena Pukui – I’m still working my way through the book of proverbs and poetry by noted scholar Mary Kawena Pukui. I’ll try to update with some of my favorites!

I’ll try to add to this list when I come across other resources I’ve found helpful!